By: Georgia Free

Warning: This article contains mentions of sexual abuse, suicidal ideation and attempts. If you need help, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org.au. If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, domestic or family violence call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

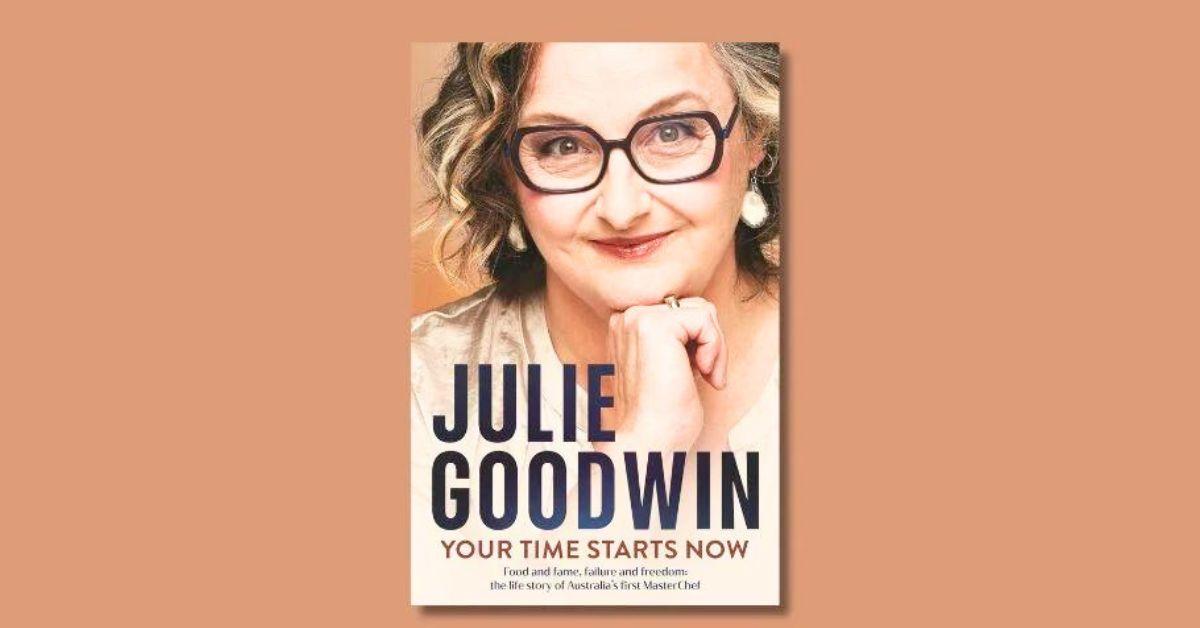

Julie Goodwin burst into our screens and into our hearts back in 2009, when she became Australia’s very first MasterChef.

Following the win, Julie was catapulted into overnight stardom.

From book deals, TV segments, breakfast radio and her own cooking school, Julie hit the ground running – and never stopped. Until one day, it all caught up to her. From mental illness to addiction, Julie has shared her full story for the first time in her memoir Your Time Starts Now.

“Swept under the rug” – a rocky childhood

For the most part, Julie remembers her childhood as happy. Although her father left when she was a toddler, she was never short on family support from her mother and grandmother.

Julie was a model student, thriving academically and talented at music and art. In Year 12, she was elected captain of Hornsby Girls High School. Her future lay before her – a sea of possibilities.

However, Julie was harbouring a secret pain from her childhood, which threatened to derail her life.

“[At seven years old], I was sexually abused,” Julie said in our interview. “Not even my best friend knew what had happened. And that memory was tucked away until I was sixteen.

“It wasn’t like some Hollywood moment, where it all came flooding back. It was always there – I just hadn’t looked at it for a really long time. And when I did, it devastated me.”

Despite her best efforts, Julie began to spiral into a deep depression – culminating in a suicide attempt around the time of her HSC examinations. However, instead of her getting help – Julie’s struggles were hidden from view.

Despite having a supportive family, Julie experienced childhood abuse.

“It was absolutely, comprehensively, swept under the rug and never mentioned again,” Julie recalled.

“Not even my best friend knew what had happened.

“It was kind of a family decision. They were worried I’d lose the school captaincy… that my reputation would be destroyed.

“I believe that decision was made to protect me, but, of course, now we know better. If there’s a kid in that kind of distress, you have to get them some help.

“Because the things you don’t cope with will stick their head up time and time again throughout your life.”

Slipping away

Julie’s belief in herself be gan to slip away. Although she enrolled in a Bachelor of Education, she dropped out of university halfway through her second year, unable to go on.

gan to slip away. Although she enrolled in a Bachelor of Education, she dropped out of university halfway through her second year, unable to go on.

“I didn’t really know why I struggled at uni,” Julie recalled.

“I shrank. I disappeared. I remember I went and bought myself this massive black overcoat from a Vinnie’s store and wore it every single day.

“And I didn’t talk to anybody.”

Julie’s belief in herself began to slip away.

“To leave uni was a really big deal. And I knew that I was letting people down, but I just couldn’t keep going.”

Julie worked a series of odd jobs, before finding herself falling into step with a youth group, run by graduates of the local boys high school. Every week, they would go out onto the streets of Sydney and feed the homeless, help the elderly around the community with yard work and run blanket and food drives.

“It was a real lesson for me in not judging a book by its cover,” Julie laughed.

“These boys… they wouldn’t have been invited by the Queen for tea, let’s put it that way. But they had hearts of absolute pure gold and they did a lot of great work.

“There was no ego in it, no Instagrammable moments. It was just bloody good blokes, doing bloody good things.”

From chaos to glory

One of those ‘good blokes’ turned out to be Mick – Julie’s future husband. They became inseparable – quickly moving from best friends, to dating – before getting married and becoming parents to three boys. They both also owned a family IT business. In short, Julie’s life was chaotic, leaving no time for creative pursuits, except for cooking.

“I’d always loved art and music, but [as a mum], they felt like selfish pursuits,” Julie recalls.

“Cooking was not a selfish pursuit – because that was for all of us.

“All my creativity, I put it all into cooking,” Julie said.

“So all my creativity, I put it all into cooking. And it ended up putting me in very good stead.”

When applications for MasterChef Australia were advertised, Julie’s friend Tash encouraged her to apply. Months later, the application long forgotten, Julie received a call from a producer inviting her to audition. Julie had no idea what was in store for her.

“I’d been watching the UK version of MasterChef. It was a very British, civilised little program,” Julie said.

“But if someone had come and told me that you would have to leave your three boys at home, you have to leave your small business that you run with your husband, you leave to leave your phone, your computer behind…I would have said that there’s no way I can do that.”

As Australia’s first Masterchef, Julie became famous overnight.

Hundreds of contestants became 50, and soon became 24. Julie travelled down to Melbourne to live in a house full of strangers – for five months. She saw her family a total of four times.

But, it was all worth it when she was crowned Australia’s very first MasterChef. And, from that moment, everything changed.

Life at double speed

Julie was catapulted into overnight stardom, with no preparation. Although she had an inkling of the size of the show while filming, it wasn’t until the final weeks of the competition that she experienced something akin to fame.

“The first moment that it dawned on me that something out of the ordinary was happening here was [at a photo shoot],” Julie remembered.

“And as we were walking back down the street, I just hear ‘Julie!’ and I turn around and there’s a road crew of these burly blokes with big beards in high-vis vests.

“And I think ‘what is happening?’

Julie was catapulted into overnight stardom.

“That’s where it really started to seep in that we were making an impact with the outside world.”

Julie’s life filled with new opportunities and commitments – from book deals, TV segments, food demonstrations, breakfast radio and a cooking school. Although she loved her new life, she could feel it rapidly begin to catch up with her.

“I remember thinking that if I didn’t take all these opportunities, they were going to dry up. I was afraid to stop running,” Julie said.

“And any time those cracks started to show, I was quite belligerent about it. I would not be told that I was anything less than purely capable of doing absolutely everything that was on my plate.”

Pushed to the brink

In late 2019, amid intense bushfires which were threatening her parents’ home, those cracks became too deep to ignore.

“It became really clear to me one particular afternoon that my family was going to be better off without me,” Julie recalled sadly.

“Obviously that’s just sickness talking right? But in the depth of my illness, it was my absolute knowledge and understanding that the only way I could relieve my family of the chaos that was me – was to leave.

“I was intercepted by angels,” Julie said.

“And I just started walking. I walked myself to the edge of Brisbane Waters [contemplating what to do next].

“And I was intercepted by angels.”

Those angels – were two strangers. Seeing Julie’s distress, they decided to sit with her, simply keeping her company. They sat for hours, in relative silence, before Julie was ready to return home to Mick.

“I called Mick and he came and got me. And once I told him where I’d been and what had happened, he took me to hospital.”

Slow road to recovery

Julie was admitted to a psychiatric unit, where she remained for six weeks. At first, she was resistant to it – believing that it was an overreaction, but soon accepted the help from others.

“It was absolutely surreal at first,” Julie recalled about the experience.

“It’s not on anyone’s list of things that they want to do when they grow up. But it was a big exercise in compassion for me.

“[I had] some insight and understanding from people experiencing mental illness in all different ways. But at our heart, we’re all so similar – we really are.”

“I am learning to be kind and gentle with myself,” Julie said.

Julie naively believed that the one hospital visit would ‘fix’ her mental illness – but as she’s since learned, the process is lifelong.

She has since been re-admitted to hospital multiple times, both for her depression and help with alcohol addiction. Her life, although still busy, has calmed down a lot – and she plans her schedule on her own terms. Her and Mick are also now grandparents to Delilah, their granddaughter, which has brought them both a renewed sense of perspective and joy.

As a proud wife, mother and grandmother, Julie finds joy in her family.

“I have learned that I have to look after myself.”

“It’s not always easy, but, you know, I have an understanding that life has ups and downs and rounds and rounds and, instead of being vicious and brutal to myself when things aren’t going so great, I am learning to be kind and gentle with myself,” Julie said.

“When I’m in a mental hospital, I’m not cooking anybody’s dinner. I’m not speaking at anybody’s engagement. I’m not on anybody’s radio show.

“I’m no good to anybody. And I have learned that I have to look after myself.”

Julie’s parting thoughts

Julie’s new memoir Your Time Starts Now has been received around the country to glowing praise and a candid recognition of a journey that is travelled by so many, especially mothers, but acknowledged by so few. Her wisdom is plentiful – but one poignant piece of advice, has resonated with many.

“We have to be allowed to say, there’s something not quite right,” Julie said.

“Until we permit ourselves to talk about it and not feel ashamed about it, the conversation is not going to go anywhere,” Julie said.

We have to be allowed to say that I can’t put my face into a smile without really working at it. That I don’t seem to be able to slow my brain down unless I have wine at the end of the day. That I don’t seem to be able to put my feet on the floor with any sense of excitement for way too many days in a row now.

“We have to be allowed to raise these things without being shamed for it and without feeling ashamed of ourselves for it. We can talk about mental health till the cows come home, but until we permit ourselves to talk about it and not feel ashamed about it, the conversation is not going to go anywhere.

“It’s one thing for us to all be standing around saying, I will hold you up. But what we need to do is be willing to be held up. And I think that’s actually harder. A lot harder.”

If you need help, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or visit lifeline.org.au. If you or someone you know is impacted by sexual assault, domestic or family violence call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

Article supplied with thanks to Hope Media.

Feature image: Julie Goodwin, Supplied

About the Author: Georgia Free is a broadcaster and writer from Sydney, Australia.